Assumpta Weekly Newsletter

Presents- Assumpta Quarterly — Edition

Article Title :The Snake and the Sovereigns.

Sub-Headline / From the Sahara’s Tracks to Africa’s Courtrooms

📅 Special Edition Release: Wednesday, February 4th, 2026

📍 Read exclusively at: assumptagh.live/

HAIR SENTA ADVERTISEMENT

https://www.instagram.com/hairsenta?igsh=MXAzOThhNGZ0Nm15dQ==

🌟 The “Wellness & Care” Campaign

Theme: Beauty that starts with how you feel.

At Hair Senta, we believe true beauty is an anchor for your well-being. It’s not just about the hair you wear; it’s about the confidence and care you pour into yourself.

Our premium extensions are meticulously sourced and treated with the philosophy that “Self-Care is Healthcare.” When you look your best, you vibrate higher.

- The Call to Action: Experience the luxury of wellness. From Accra to the world—discover the Hair Senta standard.

🌍 The “Ghana to the World” Pitch

| Feature | The Hair Senta Advantage |

|---|---|

| Origin | Proudly rooted at 24 Jungle Avenue, Accra, Ghana. |

| Quality | 100% Raw Human Hair Extensions, ethically sourced. |

| Reach | Seamless global shipping—bringing African excellence to your doorstep. |

| Community | Join over 405K followers who trust the Senta standard. |

- Hair Senta: Where luxury meets your well-being.”

- “Ghana’s finest extensions, curated for the global woman.”

- “An anchor for your beauty. A sanctuary for your care.”

- “More than a look. A lifestyle of wellness and premium quality.”

📍 Visit the Gallery

If you are in Accra or shopping online, here is how to connect with the brand:

- Location: 24 Jungle Avenue, Accra, Ghana.

- Digital Gallery: Join the 400K+ community on Instagram @hairsenta.

- Shop Online: www.hairsenta.com

Summery

The Snake and the Sovereigns

From the Sahara’s Tracks to Africa’s Courtrooms

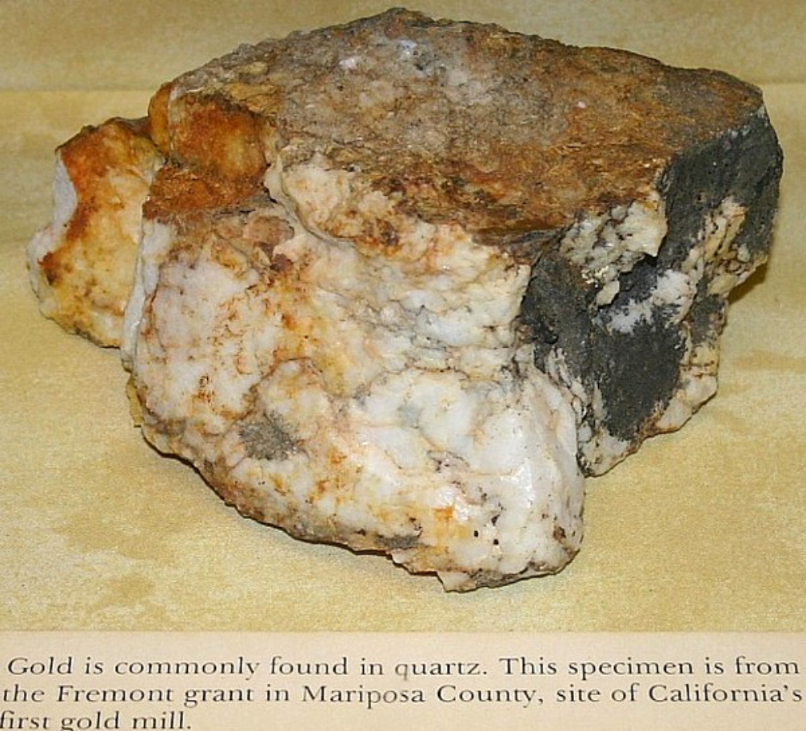

What is ore?

Ore is not wealth in its final form. It is potential — a raw substance pulled from the earth, carrying value that only becomes real after transformation. Iron ore, for example, is merely rock until it is processed, refined, and turned into iron or steel. The true power is not in extraction, but in what a nation does after extraction.

Mauritania’s story begins here — with ore, promise, and a long steel path across the desert.

In the early 1960s, vast iron ore deposits were discovered in northern Mauritania, near Zouérat. To move this ore from the Sahara to the Atlantic Ocean, one of the longest and most iconic freight railways in the world was constructed — a line stretching over 700 kilometers from the mines to the port of Nouadhibou. Locals would later call it “the Snake”: a living, metallic artery cutting through sand and silence, carrying Africa’s wealth outward.

The railway was built between 1961 and 1963 by MIFERMA (Société des Mines de Fer de Mauritanie), a company financed and technically driven largely by French and other European capital, with additional Western partners. Though Mauritania gained independence from France in 1960, the infrastructure that defined its mining economy was designed primarily for one purpose: extraction and export, not national industrial development.

The Snake did not connect cities to cities.

It connected ore to ships.

For a decade after independence, Mauritania’s iron flowed outward under this structure. Then, in 1974, the country made a bold move: it nationalised MIFERMA, creating SNIM, a state-owned mining company. Legally and formally, the iron ore — the mines, the railway, the port — became Mauritanian property.

Yet ownership did not automatically mean sovereignty in the deeper sense.

To finance expansion and maintenance, Mauritania partnered with Arab development funds, including Kuwaiti and Gulf investors. These partners did not extract the ore themselves, nor did they run the mines, but their role — like that of global buyers and lenders — reinforced a familiar pattern: Africa exporting raw materials while importing finished value.

This is where the comparison with Botswana becomes illuminating.

Botswana also inherited diamonds under colonial conditions. But instead of exporting rough stones indefinitely, Botswana renegotiated power. The state insisted on local value addition, joint control, and reinvestment into education, infrastructure, and public services. Diamonds became not just a revenue stream, but a nation-building tool. The result was political stability, visible development, and one of Africa’s strongest post-independence economies.

Mauritania, by contrast, remained locked in the raw-export trap. Iron ore left the country largely unprocessed. Infrastructure served extraction more than transformation. Wealth circulated, but did not multiply domestically at scale.

Today, a new actor negotiates differently: China.

China does not arrive asking only for ore. It often negotiates with a state-to-state mindset — bundling access to resources with roads, ports, power plants, industrial zones, and long-term infrastructure. This approach is not charity, nor without risk, but it reflects a different logic: resources are leverage, not just commodities.

And now, the story turns.

The Snake still runs through the Sahara.

But Africa is no longer speaking only through railways and contracts.

Enter the Sovereigns.

Across courtrooms, policy tables, and international negotiations, a new generation of African legal minds is reshaping how the continent defends its interests. Women like Serwaa Amihere, Esq. of Ghana, and Assumpta Gahutu, Esq. of Namibia, stand as symbols of this shift — not extracting, but protecting; not exporting raw value, but asserting legal and moral authority.

Where the Snake represents an era when Africa’s wealth moved silently outward, the Sovereigns represent a present — and a future — where Africa speaks back, writes its own contracts, and defines development on its own terms.

This is not just a story about iron ore or railways.

It is a story about who controls value, who defines progress, and whether extraction becomes destiny — or leverage.

From the Sahara’s Tracks to Africa’s Courtrooms

Case Presentation to the International Court of Justice

What is ore?

Ore is not wealth in itself. It is potential—raw matter drawn from the earth whose true value emerges only through transformation. Iron ore, extracted from Mauritania’s soil, became a cornerstone of global industry, yet for decades remained largely untransformed within the land from which it was taken.

This case is not about geology.

It is about justice, dignity, and development denied.

Following Mauritania’s independence in 1960, international investors—principally European—financed and constructed a 700-kilometer railway between 1961 and 1963, linking the iron-rich region of Zouérat to the port of Nouadhibou. This railway, known locally as the Snake, was engineered for one overriding purpose: the efficient extraction and export of iron ore.

In 1974, Mauritania nationalised the mining enterprise, creating SNIM, a state-owned company. Yet national ownership did not dissolve structural dependency. Financing arrangements, export-oriented infrastructure, and investment frameworks continued to prioritise extraction over transformation, export over industrialisation, and profit over people.

This Court is asked to consider not ownership alone, but outcomes.

Despite decades of extraction, Mauritania has remained constrained in its capacity to:

industrialise locally, add value to its own resources, diversify its economy, and fulfil the Sustainable Development Goals to which the respondent investors publicly subscribe.

This is not an isolated failure of policy. It is the result of an investment model that normalised exploitation while neglecting sustainable development obligations.

As articulated by Assumpta Gahutu, Esq., Counsel for the Applicants:

“Exploitation is a power wielded equally by all investors—Black or white, African or European—who have no living faith in the human potential for good.

When exploitation is accepted as the law of investment, it pervades the human being, degrades skills, and isolation becomes the norm of action.

The world is in desperate need of compassionate people who care for others and for the good we can offer to one another.

There must be a recognition of the sacredness of human personality, deeply rooted in any political and investment heritage, with the conviction that every Black man is the heir to a legacy of dignity and worth.

Exploitation is a violation that stands diametrically opposed to the principle of the sacredness of human personality.

It debases the Sustainable Development Goals.

The tragedy of exploitation is that it treats men as means rather than ends, thereby reducing the people of Mauritania to things rather than persons.”

This case does not allege that all investors were unlawful.

It asserts that lawful investment without ethical restraint, developmental intent, or respect for human dignity becomes structurally unjust.

The Sustainable Development Goals are not aspirational ornaments. They are commitments—requiring investors to:

- Promote inclusive growth,

- Support local value creation,

- Strengthen human capital, and respect the intrinsic worth of affected communities.

When infrastructure is designed solely to extract,

when financing excludes local transformation,

when profits flow outward while poverty remains inward, development is not delayed—it is denied.

Alongside Serwaa Amihere, Esq. of Ghana, Counsel submits that this Court must affirm a clear principle:

👉 That investment which ignores human dignity, suppresses national development, and reduces people to instruments of profit is incompatible with international law’s evolving conscience.

The Snake still runs through the Sahara.

But today, it is met by the Sovereigns—African legal minds who stand not against investment, but against exploitation disguised as development.

This case asks the Court to recognise that true prosperity cannot be built on extraction alone, and that Africa’s resources must no longer travel farther than Africa’s dignity.

The Extraction Audit: Why Wealth Often Leaves Only Dust

Many ask the same hard question: Was the system designed to keep the nation dependent?

The short, honest answer is yes. The infrastructure was built to move ore, not to build a nation. While ownership is now Mauritanian, the structural “gravity” of the global market still pulls value outward.

1. The Design: Extraction over Integration

The system was engineered for a very specific path: Mine → Railway → Port.

- The Goal: Efficiency for the buyer and stability for the investor.

- The Gap: It neglected downstream factories, diversified cities, and broad middle-class prosperity. The “Snake” connects wealth to ships, not citizens to opportunities.

2. The Raw-Export Trap

Mauritania earns revenue, but it stays dependent. Why?

- Low Value: Exporting raw ore means accepting the lowest possible price point.

- Leakage: Profits “leak” back to the Global North through shipping, insurance, and specialized equipment.

- Isolation: Infrastructure serves the export of rocks, not the internal movement of people and goods.

3. The Sovereignty Gap

Even with state ownership (SNIM), true sovereignty is elusive when a nation relies on foreign buyers, foreign finance, and foreign technology. Extraction without transformation (local processing) keeps a country’s economy “alive,” but it does not make it “strong.”

The Painful Truth: Extraction alone cannot fix governance weaknesses or social inequality. Without political courage to force local value addition, the wealth leaves, and the dust remains.

4. The Path Forward: From Ore to Authority

Dependency is not a permanent sentence. To break the cycle, the strategy must shift toward:

- Mandatory Local Processing: Moving from raw ore to refined steel.

- Human Capital: Investing mining dividends into education and high-tech skills.

- Diversification: Using mining as a battery to jumpstart other sectors, rather than a crutch to lean on.

The Sovereigns’ Dialogue: Negotiating the Future

Serwaa Amihere, Esq.: Good morning, good afternoon, and good evening to our readers and listeners joining us from every corner of the globe. Welcome to this special edition of our dialogue. I am Serwaa Amihere, a legal practitioner from the vibrant shores of Ghana, a nation that knows all too well the weight of gold and the complexity of its cost.

Beside me today is a woman whose intellect is a beacon for the continent—Assumpta Gahutu, Esq., a distinguished legal mind from Namibia, where the desert meets the ocean and the diamonds meet the law. We stand here not just as lawyers, but as “The Sovereigns”—part of a generation of African legal minds dedicated to shifting the continent from a site of extraction to a seat of authority.

Assumpta, I want to first start with you in this explosive dialogue. Welcome. Your recent work has fundamentally challenged our understanding of trade and investment. You’ve moved us past the academic jargon to reveal what you call “Predatory Permanence.” It is a chilling concept.

Assumpta, I want you to address our panel and our readers worldwide with the clarity found in your newsletter. Can you elaborate on this vision of the “Invisible Table” and how extraction has evolved into systemic management?

Assumpta Gahutu, Esq.: Thank you for the opportunity and for that warm welcome, Serwaa. It is an honor to stand with a sister-in-law from Ghana as we dissect these truths.

My facts are rooted in the contracts I review and the history we live. My view is this: We are witnessing a transition from the “Army to the Arbitrator.” In the past, if a power wanted Africa’s resources, they sent soldiers. Today, they send a 50-year lease agreement with an “investor-state dispute settlement” clause.

This is the Generational Debt of Consent. When we sign these long-term mineral leases today, we are not just selling rocks; we are mortgaging the policy space of a Namibian or Ghanaian child born in 2045. That child never consented to be a “supplier” only, yet the law will tell them they are “locked in.” If they try to build a factory on that land in thirty years, they are told they are “defaulting” on an international treaty signed before they were born. That is the legal checkmate.

Serwaa Amihere, Esq.: Thank you, Assumpta. That is a powerful and sobering opening. The idea that a signature today acts as a “checkmate” for a child born two decades from now is a perspective we rarely hear in economic summits. You’ve framed the “legal cost” as something much heavier than money—it’s the loss of future agency.

Assumpta, I’m particularly struck by your point on “Security Meetings vs. Price Settings.” Could you share your thoughts on why Africa is invited to talk about “conflict” but excluded when it comes to “commodity pricing”?

Assumpta Gahutu, Esq.: Thank you for asking that, Serwaa. It goes to the heart of the “Invisible Table.”

The facts are clear: Global powers frequently invite African heads of state to discuss “Security”—terrorism, migration, and “stability.” But notice what is missing. We are almost never invited to the tables where the Global Commodity Index is set or where the rules of the World Trade Organization are whispered into being.

This is because, in the eyes of the current global order, Africa is a “variable,” not a “partner.” If you control the price of the ore and you control the law of the sea, you don’t need to colonize the land. You simply “manage” it. This leads to what I call “Managed Africa”—a continent kept just stable enough so the “Snake” (the railway) keeps moving, but never prosperous enough to stop exporting raw value and start competing. How can they talk about us without us? They see our resources, but they refuse to hear our circumstances.

Serwaa Amihere, Esq.: Thank you, Assumpta. “Managed Africa”—stability without prosperity. It’s a haunting image of a railway that never stops while the people beside the tracks never move forward.

Assumpta, to bring this home for our readers, what are your thoughts on how we “widen the lanes”? If the policy lanes are currently narrowed by these old structures, how do the “Sovereigns”—the lawyers and policy makers of today—begin to write a different contract? Can you share your thoughts on the first step toward reclaiming that seat at the table?

The Sovereigns’ Response

Assumpta Gahutu, Esq.: “Serwaa, you’ve hit the nail on the head. For too long, we have been ‘passengers’ on our own economic train—enduring the dust and the heat while the value is locked away in the front office. To ‘widen the lanes,’ we have to stop signing contracts of acquiescence and start signing contracts of partnership.

If we want to reclaim our seat at the table, we must move beyond ‘royalties’ and start demanding ‘relevance.’ Here are the three legal pillars I believe every African Sovereign must demand in modern extractive contracts:”

1. The ‘Value-Addition’ Mandate (Local Beneficiation)

”We must stop exporting ‘dirt’ and start exporting ‘products.’ A standard clause should mandate that a specific percentage of raw materials—be it Mauritanian iron, Ghanaian gold, or Namibian diamonds—must be processed or refined within our borders. If they want the resource, they must build the factory here. This turns a ‘train to the coast’ into a ‘hub for the region.'”

2. The ‘Infrastructure Interconnectivity’ Clause

”The Mauritanian train is a tragedy of ‘single-purpose’ engineering. Future contracts must require that any industrial railway or road built by a multinational must be ‘dual-use.’ It must be designed to connect local markets and transport civilian goods, not just ore. We must legally compel the ‘Snake’ to serve the village, not just the vessel at the port.”

3. The ‘Dynamic Equity’ Ratchet

”Static contracts are the enemy of progress. We should implement clauses where the state’s equity or tax share increases automatically as the project hits certain profitability milestones. This ensures that when the global price of iron ore or gold spikes, the people of the soil see the windfall—not just the shareholders in London or Paris.”

The Dialogue Continues: Exploring the “Ghana-Namibia Connection”

Assumpta Gahutu, Esq.: “But Serwaa, I’m curious to see if this ‘Managed Africa’ pattern holds true in the West. In Ghana, you have one of the oldest gold sectors on the continent. Does the ghost of the ‘Snake’ haunt your mines as well? Are the lanes being widened there, or are the tracks still only leading one way?”

Serwaa Amihere, Esq.: (Reflecting on the Ghanaian experience) “It’s a striking parallel, Assumpta. In Ghana, we’ve seen that even with independence, the ‘extractive architecture’ remains stubborn. For decades, our gold left as bullion, leaving behind environmental scars but limited industrial depth. However, we are fighting back with the ‘Gold for Oil’ policy and new local content laws—trying to turn that one-way track into a circular economy that fuels our own growth.”

Ore Train is more than a tale of hardship; it is a Case Study in Contractual Architecture. To a lawyer, the train tracks are physical manifestations of a “Concession Agreement”—the legal documents that dictate who owns the soil, who profits from the subsoil, and who bears the cost of the transit.

Here is how we translate the “Snake of the Desert” into the language of the courtroom and the boardroom for the Assumpta Quarterly Newsletter.

The Legal Anatomy of the “Snake”

1. The Doctrine of Extraction vs. Development

Historically, colonial-era mineral agreements were built on the Doctrine of Absolute Ownership for the concessionaire. The legal “lanes” were intentionally narrowed to focus on output (tonnage) rather than outcome (national wealth).

- The Lawyer’s View: The train’s 704 km route is a “locked-in” infrastructure asset. In legal terms, this is an Enclave Project—an economic activity that has no links to the local economy, designed specifically to bypass the local population and deliver value directly to an export terminal.

2. Sovereign Risk and the “Stabilization Clause”

One reason the “Snake” still runs the same way it did in 1963 is the Stabilization Clause. These are provisions in mining contracts that “freeze” the law of the host country at the time the contract is signed.

- The Impact: If Mauritania tries to pass new environmental laws or safety regulations for those riding on top of the wagons, the mining companies could theoretically sue the government in international arbitration for “breach of contract.”

- The Challenge: As lawyers, our job is to draft Flexible Governance Frameworks that allow a nation’s laws to evolve without bankrupting the state.

3. The Liability of the “Lifeline”

The fact that people ride on top of ore wagons creates a complex Tort and Liability nightmare.

- The Paradox: Legally, these people are often “trespassers,” yet the state-owned mining company (SNIM) allows it because it is a vital social service.

- The Legal Fix: A modern lawyer would ask: Where is the Community Development Agreement (CDA)? Modern law should mandate that the “Right of Way” for a mineral train must include a “Duty of Care” for the corridor’s inhabitants.

The Sovereigns’ Strategy: A Legal Manifesto

In the dialogue between Serwaa Amihere, Esq. and Assumpta Gahutu, Esq., they are essentially discussing a transition from Contract Management to Resource Sovereignty.

| The Old Legal Model (The Snake) | The New Legal Model (The Sovereigns) |

|---|---|

| Enclave Infrastructure: Built only for ore. | Multi-Modal Infrastructure: Built for ore, trade, and people. |

| Tax Holidays: Revenue lost to attract investment. | Progressive Royalties: Revenue scales with global prices. |

| Raw Export: No requirement to process locally. | Beneficiation Mandates: Processing must happen in-country. |

| International Arbitration: Disputes settled in London/Paris. | Regional Jurisdiction: Disputes settled in African hubs. |

Closing Argument: Rewriting the Rails

As lawyers, we know that the law is the track upon which the economy runs. If the track is laid only for extraction, the wealth will always leave.

Serwaa and Assumpta represent the new “Engineers of the Law.” They are not just interpreting old contracts; they are drafting the new ones that will ensure the next three-kilometer train doesn’t just carry iron ore—it carries the aspirations, the safety, and the prosperity of an entire continent.

The Sovereigns’ Dialogue: Reclaiming the Narrative

Serwaa Amihere, Esq.: Thank you, Assumpta. Your point on “Managed Africa” hits a nerve. It reminds me so much of the situation in Ghana, particularly in our gold sector. For decades, we have been the “Gold Coast,” yet for a long time, the “gold” stayed in the name while the value flowed through the same narrow lanes you described.

Even as we moved toward more sophisticated agreements, we found that the pattern held: we provided the raw wealth, while the refining, the jewelry markets, and the financial derivatives—the “real” money—happened in Zurich, London, and New York. We were celebrated for our “stability,” but that stability was often a synonym for “predictable supply” for the global market.

Assumpta, I want to pivot to the “Sovereigns’ Strategy.” We are not just here to lament; we are here to lead. If we are to “widen the lanes” and stop the generational debt of consent, we need new tools. Can you share your thoughts on the specific legal clauses that African nations must start demanding in every contract to ensure we are no longer just “variables” in an equation?

Assumpta Gahutu, Esq.: Thank you for the opportunity to get practical, Serwaa. To move from being “managed” to being “sovereign,” we must change the DNA of our contracts. My view is that we need three non-negotiable pillars:

- The “Sunset on Rawness” Clause: We must stop signing 50-year deals for raw exports. Every contract should include a mandatory “Value-Addition Escalator.” For example, by year five, 20% of the ore must be processed locally; by year ten, 50%. If the investor doesn’t build the refinery, they lose the concession. We must legislate the “transformation” we talk about.

- The “Dynamic Stability” Clause: Investors love “stabilization clauses” that freeze the law for 30 years. We must replace these with “Periodic Review Triggers.” Every 5 to 7 years, the contract must be re-evaluated against current global prices and the country’s development needs. Sovereignty cannot be frozen in time.

- The “Local Integration” Mandate: Not just jobs for laborers, but equity for local firms and technology transfer for our engineers. The infrastructure built—the railway, the power—must be “dual-use.” It must serve the mine, yes, but it must also be designed to connect our farmers to our cities.

Serwaa Amihere, Esq.: Thank you, Assumpta. Those three pillars—Transformation, Review, and Integration—are the blueprint for a new era. They move the “Snake” from a single-purpose extraction line to a multi-purpose national asset.

It is clear that the “Sovereigns” are no longer content with being guests at a table they didn’t set. We are now the architects of our own houses.

Serwaa Amihere, Esq.: This brings us perfectly back to the heart of our discussion today: The Snake and the Sovereigns. From the Sahara’s tracks to Africa’s courtrooms, we are seeing a shift in where the “battle” for the continent is being fought.

Assumpta, you spoke about the “Snake”—that 700-kilometer metallic artery in Mauritania designed to pull iron ore out of the desert and into the holds of waiting ships. For decades, the Snake represented a victory of engineering but a defeat of agency. It was a line that went from a hole in the ground to a port, bypassing the development of the people entirely.

But now, the “Sovereigns” are the new infrastructure. You and I, and the legal minds across the continent, are the ones building the new “tracks”—not of steel, but of law and policy. Assumpta, can you share your thoughts on how we transition from the physical “Snake” of the 1960s to the “Sovereign” courtrooms of the 2020s?

Assumpta Gahutu, Esq.: Thank you for that framing, Serwaa. It is a profound transition. The “Snake” was a product of an era where power was measured in the ability to move heavy things. Today, power is measured in the ability to move ideas and terms.

My view is this: The courtrooms and the negotiation tables are the new “Zouérat” (the mining center).

- The Old Way: We fought over who owned the ad pop slop shovel.

- The New Way: We fight over who owns the data, the pricing mechanism, and the intellectual property of the extraction process.

When we take these cases to international courtrooms, we aren’t just arguing about a breach of contract; we are arguing about the right of a nation to evolve. If the “Snake” was built to be rigid and fixed, the “Sovereign” legal framework must be fluid and protective. We are moving from the Sahara’s tracks—which only go one way—to the courtroom, where we can finally demand a U-turn for the value that has been leaving our shores.

Serwaa Amihere, Esq.: Thank you, Assumpta. “The right of a nation to evolve”—that is a phrase that should be etched into the entrance of every Ministry of Justice on the continent. It challenges the very idea of “Managed Africa.”

Assumpta, before we conclude this segment, I want to ask: when you look at that 700-kilometer line in Mauritania and then you look at the faces of the young African lawyers entering the field today, do you see the “Snake” being tamed? Can you share your thoughts on whether the law is truly strong enough to redirect the wealth that has been flowing outward for over sixty years?

Assumpta Gahutu, Esq.: Thank you for the opportunity to speak to the next generation. My facts are these: The law is only as strong as the people who sit at the table to defend it.

The “Snake” isn’t just a train; it’s a mindset of “this is how it has always been.” We tame the Snake the moment we refuse to sign a contract that doesn’t include our children’s future. The law is the only tool we have that can stop a train. It is the only thing that can tell a global conglomerate, “No, the tracks stop here until the value stays here.”

So yes, I am hopeful. The “Sovereigns” are writing a new map where the tracks don’t just lead to the ocean—they lead back home.

Serwaa Amihere, Esq.: Thank you, Assumpta. Truly, the tracks must lead back home.

You have moved us from the mechanics of contracts to the sanctuary of the human spirit. Your words remind us that beneath every iron rail and every ton of ore lies the “sacredness of human personality.”

Assumpta, I want to give you the floor once more to conclude this profound opening. How do we reconcile this legal struggle with the ethical necessity to treat our people as ends in themselves, rather than mere tools for extraction?

Assumpta Gahutu, Esq.: Thank you, Serwaa. To our readers worldwide, my final view is this: Exploitation is a power wielded by any investor—regardless of origin—who lacks faith in human potential. When exploitation is accepted as the “law of investment,” it doesn’t just drain the soil; it degrades the soul, isolates the worker, and debases the very Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) we claim to uphold.

The tragedy of the “Snake” in Mauritania is not merely that it moves ore, but that it treats the Mauritanian people as means rather than ends—reducing human beings to “things” in a global ledger.

We do not allege that all investment is unlawful. We assert that lawful investment without ethical restraint is structurally unjust. The SDGs are not aspirational ornaments; they are a commitment to:

- Promote inclusive growth,

- Support local value creation,

- And respect the intrinsic worth of the communities where these resources reside.

When infrastructure is designed solely to extract, and profits flow outward while poverty remains inward, development is not delayed—it is denied. This is why the Sovereigns have risen. We stand not against investment, but against exploitation disguised as development.

Serwaa Amihere, Esq.: Thank you, Assumpta. A powerful and necessary distinction. The law’s “evolving conscience” can no longer turn a blind eye to the reduction of a person to a mere instrument of profit.

As we close this inaugural dialogue, let us reflect on the duality of our journey:

The Snake and the Sovereigns

From the Sahara’s Tracks to Africa’s Courtrooms

The “Snake” still cuts its path through the shifting sands of the Sahara, a metallic reminder of a century of extraction. But today, the silence of the desert is broken by the voices of the Sovereigns. We are a generation of legal minds—from Ghana to Namibia, from Mauritania to the world—who insist that Africa’s resources must no longer travel farther than Africa’s dignity.

Assumpta, thank you for your courage and your clarity. It has been an honor to share this platform with you.

Assumpta Gahutu, Esq.: Thank you, Serwaa. The honor is mine. To our readers across the globe: the tracks are being rewritten. Sovereignty is no longer just a flag; it is the contract we write today for the child born tomorrow.

Serwaa Amihere, Esq.: And with that, we thank you for joining us. Let this be the start of a global conversation on what it truly means to invest in the dignity of a continent.

Is a nation truly at peace if its “stability” is bought at the price of its children’s prosperity? Is stability without the power to define your own future actually peace, or is it just a very quiet form of extraction?

Thank you for joining this dialogue. We look forward to hearing your thoughts on how we can all work to widen the lanes of African agency.

An introduction to the Soka Gakkai and Nichiren Buddhism. Where do the teachings originate from? What is the philosophy of Buddhism? How do Soka Gakkai members apply it in their daily lives?

The Soka Gakkai is a global community-based Buddhist organization that promotes peace, culture and education centered on respect for the dignity of life. Its members in 192 countries and territories study and put into practice the humanistic philosophy of Nichiren Buddhism.

Soka Gakkai members strive to actualize their inherent potential while contributing to their local communities and responding to the shared issues facing humankind. The conviction that individual happiness and the realization of peace are inextricably linked is central to the Soka Gakkai, as is a commitment to dialogue and nonviolence.

Subscribe to our channel: / sgivideosonline

Visit our website: https://www.sokaglobal…

Like us on Facebook: / sgi.info

Follow us on Instagram: / sgi.info

Follow us on Twitter: / sgi_info

https://www.instagram.com/melangebypistis?igsh=YjNidmp3MGcwcjlu

It is a pleasure to acknowledge Joselyn Dumas for her well-deserved win of the IMAGINE Prize! This recognition highlights her role as a true style icon who gracefully bridges the gap between heritage and modern luxury.

Her outfit is a stunning example of how contemporary African design can command attention in any setting, including a high-end corporate environment.

Outfit Breakdown: Melange by PISTIS

The ensemble is a masterclass in structure and textile artistry:

- The Silhouette: A chic, fit-and-flare mini dress. The structured bodice features a high neckline with a delicate teardrop cutout and lace-up detailing, providing a sophisticated yet modern edge.

- The Fabric: The dress is crafted from a rich, metallic brocade-style textile. It features an intricate, multidimensional pattern that resembles abstract brushstrokes or stone textures in shades of emerald green, royal purple, and burnished gold.

- The Styling: She pairs the bold dress with minimalist forest green ankle-strap sandals, which elongate the leg without competing with the dress’s vibrant pattern. Her hair is styled in voluminous, polished waves that complement the “royalty” aesthetic PISTIS GH is known for.

Why It Works for “Corporate Confidence”

You mentioned the fit and confidence; this look works for a creative corporate or “power” setting because:

- Structure: The crisp tailoring of the skirt and the modest neckline maintain a professional boundary.

- Texture over Print: Using woven textures rather than loud prints adds a level of “quiet luxury” and depth that feels very executive.

- Cultural Heritage: It honors African craftsmanship (via PISTIS GH) while adhering to a globally recognized professional silhouette.